Motivation

I studied Drama at Manchester University, and it was a given that every year some group of students would form a company and put on a show at the Edinburgh Festival. But in 1997, two of my contemporaries – Chris Sudworth and Richard Coupe – went one step further and got funding to run the Manchester Student Playwriting Competition, convincing some people from BBC Manchester and the Royal Exchange Theatre to act as judges. The first winner of the competition was a play called Life’s a Gatecrash, which won a Fringe First in Edinburgh and created a flurry of interest in its writer.

Chris was a friend, and as he knew I wrote he had mentioned the competition to me when it launched. My calling card play Wolfsong was entered in 1997, and came runner-up to Gatecrash. Then I heard every detail of the plays success from Helen Copley, the female lead in the play and one of my oldest friends. When Chris told me the play had recouped enough revenue to fund the competition for a second year, I was already determined that my entry would be the next Gatecrash.

Inspiration

The play was written during my early “issues” period that led to me writing about child abuse and HIV. It was inspired by Tori Amos’ Me and a Gun, a song itself inspired by her own rape. The date that the female lead is taken on by her attacker is – up to one crucial point – the first date I ever had, and the character of Neil is a homage to Neil Gaiman: his interpretation of Genesis from the Sandman comic makes an appearance in the play.

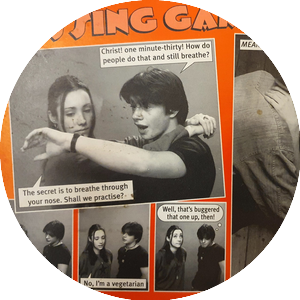

The central motif of actors playing multiple roles delineated by minor costume changes was an expansion of a similar idea in my previous play, The Kissing Game. It developed further after my exposure to the alienation principles of Bertolt Brecht, which makes the play sound much more intelligent and thoughtful than it really was. I determined to use on stage captions to continue the alienation, but these didn’t make it into the final production.

Getting the Story

The first draft of the play was originally written in the period post-Hello? when I decided I was definitely going to be a playwright. There were a number of plays written in that period and hastily sent off to the Leicester Haymarket Theatre, eventually leading to me joining their first writing group. Like most of them, it wasn’t very good: the original Night on the Tiles had much longer scenes and a full cast playing one role each, and moved at a snails pace.

After The Kissing Game had been produced, I went back to Night on the Tiles and rethought it in relation to what little I had learned. The storyline of a date rape and the female lead’s eventual determination to survive it stayed the same, but I wanted to make the play itself more interesting. The scenes got shorter, and I engineered a pivot around the break between Acts One and Two: the first Act was told in flashback by the female lead as she sat on her kitchen floor after the rape, and Act Two was told as a flash forward from that same point.

Editorial

The play was entered in the competition, and one day I bumped into Chris Sudworth on my way to a lecture and was told that it had won. Chris was excited about the play, and had decided to direct it himself. I didn’t involve myself too closely in the casting or rehearsal process, and the only change I needed to make to the script was to approve the remove of the inter-scene captions – mostly on the grounds that the budget wouldn’t stretch to the TV screens I had envisaged displaying them.

What Happened Next?

A Night on the Tiles had a full run in the 1998 Edinburgh Fringe Festival, being performed at the same venue Gatecrash had been such a success at. I couldn’t attend for the entire run, but made it up to see the play as often as I could. It was reasonably well received, but didn’t get a review in the Scotsman and wasn’t shortlisted for the Fringe First award. It was clear that it wasn’t going to be as big a success as Life’s a Gatecrash had been, and it didn’t make enough of a profit to allow the Manchester Student Playwriting Competition to run for a third year.

However, the play did make an impact somewhere else: once I returned to Manchester, two of the competition’s judges got in touch to talk to me about my writing. One was with the Royal Exchange Theatre, and eventually led to me joining their First Eleven writers’ group. The other was a drama producer with BBC Radio, and asked me for some ideas for radio plays. Being young and over-eager, I sent her a copy of Hello? and every idea that entered my mind at that moment. I spent no effort to develop them properly, and so of course neither did the BBC. The experience taught me to take my time when I’m asked for ideas, and work out the core of the story rather than pitch the initial starting point.