Invitation

In 1994, my first play Hello? had just finished a two week run at the Old Red Lion theatre and picked up some positive reviews. It’s director, Tim Crook, asked if I had any other plays that he might be able to put on. Hello? was the first play I’d written, but in the time between me entering it in the Woolwich Young Radio Playwright’s Competition and it finishing I’d decided I was going to be a playwright. I had two scripts I could show Tim – an Angela Carter adaptation called Wolfsong and a HIV issue-play called A Game of Risk, after the popular board game.

Working on an adaptation of Angela Carter’s ‘Wolfsong’ was an excellent decision and I am sure he would have gained so much from dramatizating the writing of such a significant writer. But it is unlikely IRDP would have been able to afford the rights to produce a stage version.

This is a fair point, but what it makes me realise the importance of clarity in a pitch: whenever I tell people about Wolfsong, I always talk about it in relation to the Angela Carter story that inspired it. But that story is a retelling of Little Red Riding Hood, and the only real connection Wolfsong has to it is that it is too. By mentioning Angela Carter, I make potential producers worry about adaptation rights and make it more likely they will pass: I should instead talk about Little Red Riding Hood.

But Tim never got the chance to turn down Wolfsong: despite me thinking Wolfsong the stronger script, I sent him A Game of Risk. I second-guessed his tastes, and decided it was more the kind of thing he might take.

Inspiration

The play was initially inspired by the The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy song Positive, a stream of consciousness from a character on his way to get an AIDS test. It was one of the first times I consciously decided to do some research in my writing, and I wrote to the Terrance Higgins Trust – pre-internet – to ask them to send me some information. This mostly became background, but did inspire some of the things that happened in the play.

There was also some inspiration from watching Theatre de Complicite’s The Three Lives of Lucy Cabrol. This was an extraordinary play, performed as total physical theatre where actors took on characters in an instant and threw them off again. It has remained an inspiration to this day, but in this case what it gave me was the idea of a cast of two playing multiple roles.

Getting the Story

The major incidents of the first draft of the play remained mostly unchanged: boy meets girl who then discovers she might be HIV+ but true love wins out. My intention was to write a fairly traditional romance, with – and believe me it’s hard to write these words – the HIV diagnosis as the misunderstanding that keeps the lovers apart until the final scene. I wasn’t trying to make any statement on sexual morality, or the politics of HIV as a disease. I was too naïve and unskilled to understand that an audience would of course look for those things in this story, and – worse – find something that looked like them.

I’m not a great believer in “Write what you know”, but the play did teach me the importance of admitting to yourself when you don’t know enough about a subject. I was writing about teenagers getting drunk, going to parties and having sex … all subjects that I didn’t have any first-hand experience of. I knew more about the risks of pregnancy and infection than I did about lust and passion, and my characters needed to be the complete opposite. I should have admitted that it wasn’t going to work, and either found out more or abandoned altogether.

I respect this reflection, but would disagree about the point as a conclusion for his experience. If there were problems with the script and the play received only ‘one scathing review, and did not do fantastically well,’ I think I, as the director should take my share of personal responsibility for that.

I was very pleased with the production of ‘The Kissing Game.’ It had wit, humour, charm and, of course, it was a sincere issue play. I would have had no interest in whether Paul knew less about ‘lust and passion’ than ‘the risks of pregnancy and infection.’ If the play did not have authenticity, this would have been self-evident during the first rehearsed reading.

Perhaps this is fair, but at the end of the day the script needed more work. But I finished my draft and moved on.

Outside Help

This first version of the play was fairly similar to the final version: the only difference was that only the actress playing Tina had a dual role, also playing The Boy. I again took my draft to show to Jez Simons: Jez was a playwright who had written for Eastenders, and was – in those pre-internet days – the only other writer I knew in the whole world. He read the script and suggested that the actor playing Mark should also have a dual role, playing The Girl. This led to some rewriting, but only as much as was required to add her in.

Editorial

After reading the play, Tim Crook was enthusiastic about producing it.

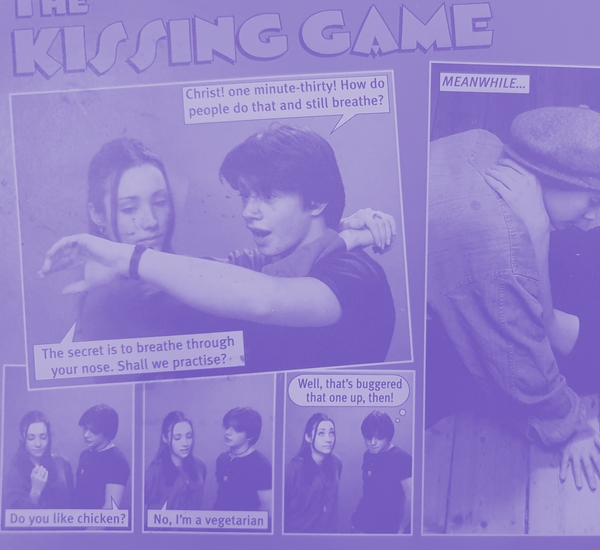

It was a remarkable play. The concept of four characters: two pairs of teenage boys/girls performed by two actors taking on dual characterization was fascinating and captivating. It inspired the two professional actors cast, Danny Newman and Emma Owen-Smith, and they conducted considerable research and contributed great amounts of professional creativity to the interpretation.

He suggested a name change, to The Kissing Game, and also suggested it needed a scene where Mark reflected on finding out Tina might be HIV+. This was duly written, and became one of my favourite scenes.

We went into rehearsal with Julie Smith and Danny Newman, but part way through Julie had to drop out and we auditioned for her replacement. Tim favoured a TV actress for the role, but when he asked my opinion I said I’d preferred Emma Owen-Smith: Tim had been partly thinking of the audience she might bring with her, but deferred to my preference. He asked me if I knew any songs that might be good for the play, and bought a good handful of albums I thought were good and tangentially mentioned relationships. None of them suited the play, and instead a much better soundtrack was suggested by the cast.

I think both these incidents made Tim start to realise that he wasn’t dealing with a brilliant commercial mind, or even a rough talent with a total vision of the play.

I had a fantastic time sleeping on designer Liz Putland’s sofa and attending rehearsals in the day. Tim paid an allowance for me to live on while I was there, and I don’t think he ever really got his money’s worth of input or support. One night, Liz said that I could be a good writer one day, once I worked out what I wanted to write. It made me wish I’d shown the script to her back at draft stage.

What Happened Next?

The play went on for four weeks at Tristan Bates Actors Centre in 1996. It received one scathing review, and did not do fantastically well.

Dale had written another play for his generation, but unlike ‘Hello?’ its appeal and resonance did not move beyond the potential audience of 13 to 18. As another director who read the script quite sensibly observed, it was excellent and ideal for TIE ‘Theatre In Education’ - a significant art and education movement originated by the Belgrave Theatre in Coventry in 1965.

That was, I think, the core of it. I was writing for my peers and then chasing an audience who just didn’t go to West End theatre in the 90s. And at the same time, I wasn’t particularly writing what I wanted to do. I was trying to write a witty episode of Grange Hill, when my heart was in magical realism and odd fantasy. Probably that wouldn’t have found its audience either, but then perhaps the experience wouldn’t have felt like such a missed opportunity if I’d gone with my heart.

At the last performance, Tim presented me with a book called The F Word, which was both a reference to the production – F the critics, we’d had fun – and also to Tim’s advice that if I wanted to be a playwright, I should really learn to love more graphic language. We never worked together again.

I’d like to say I learned a lot of lessons about my writing from The Kissing Game, but although the lessons were there to learn, I didn’t pick them up until much later. The next thing I wrote was another issue play, and it was written in pretty much the same way that The Kissing Game was.

Did I need to press on Dale that as a professional writer he needed to draft and redraft if his instinct and cogent writer’s self-analysis told him to do so and that writing is hard, hard, very hard work? On reflection I probably did. But my omission would have been due to my reluctance to patronize him in any way. I have often been criticized for being too kind as a director.

The problem was that early success had taught me that I didn’t need to draft or redraft – didn’t even really need to work that hard – and it took a lot of rejections for me to start to realise that you only pull that trick once. You might manage to write something good enough that people will ignore the rough edges for your first work, but your second has to be better. If you don’t do the hard work, you can’t improve. And there will always be someone better, more worthwhile, pushing up behind you.