Doctor Who fandom online: one man's experience

To the best of my knowledge, as I sit here and write this in March 2009, I am celebrating my first decade of internet use. Some time in 1999 – and Google cannot help me here – I joined the group alt.drwho.creative. From there, I graduated to rec.arts.drwho, and spent an inordinate amount of time arguing the merits of various BBC Books featuring The Doctor.

I know that this makes me a dinosaur. I still own underwear that’s been around longer than I’ve been online, but in internet terms I’m a Cro-Magnon wondering where all the mammoths went. There will be people reading this who’ve never had to use a dial-up account to try to convince someone on the other side of the world that they’re wrong about canon. People who find the whole idea of newsgroups as quaint and olde worlde as I find the idea of using the phone book as anything other than a doorstop.

To try and give those people an idea of what it was like back then, I’ve drunk a bottle of wine and am going to type until I fall asleep. With CAPS LOCK on RANDOM and teh spell-CHECK disabeld.

But what’s important to remember is that I’m not the start of it: even before I got involved, there was an online Doctor Who fandom – right from the internet’s earliest days, even. There is a prehistory to fandom that predates my arrival in it, my birth even – which is a common element that unites the majority of fans today: no matter how long you’ve been a fan, there’s stuff that went on before, a time when they did things differently.

In the eighties, when I started watching Doctor Who, fandom was carried out in the field – meetings in pubs or playgrounds, travelling the length and breadth of the country to attend conventions, talking to other fans face to face. And part of the main motivation for doing that was to excavate your own personal prehistory.

“I used to go to conventions in the 1970s and early 1980s. Most conventions were run in London by the Doctor Who Appreciation Society (DWAS), so it was usually an overnight coach trip or train ride,” says Peter Anghelides when I ask him – via the internet, of course. “This was in the days before DVDs, and when a blank video tape cost ten pounds. As well as talking with fellow fans, you could watch old episodes of Doctor Who — perhaps seeing something you hadn’t seen since its original transmission.”

Fans banded together, forming organisations like DWAS in part so that they could gather information about the show that wasn’t available from official sources. Justin Richards, a member of DWAS in its earliest days, explains:

“The DWAS Reference Department had synopsis sheets for every story - just a 2-page photocopied pamphlet with some black-blob photos and the Radio Times blurb and cast listings. You can’t begin to understand how exciting that was. We didn’t have video, so we swapped audio recordings – cassettes … there wasn’t any email, so everything was by GPO letter and parcel.”

But while all that was going on, there was something growing that would change everything: something called ARPANET.

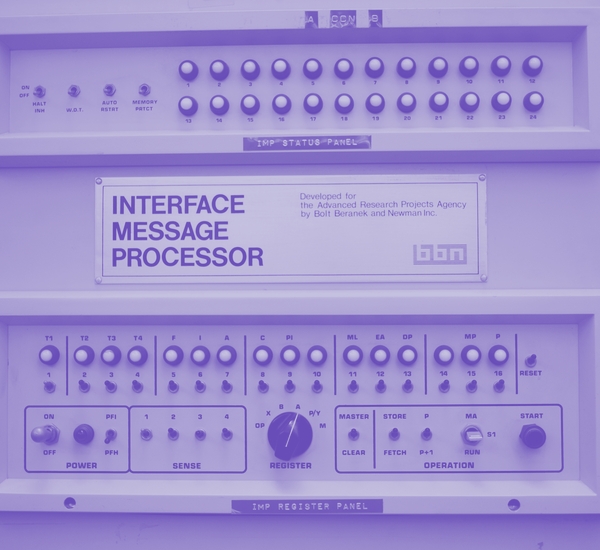

Much comment has been made about the US military’s involvement in developing the fledgling internet – probably because the synergy with the battlefield the web then became is somewhat pleasing – but most of the actual development was done in the country’s universities. In 1969, the University of California and the Stanford Research Institute established the first ARPANET connection – that is, the first network to use the same basic set up as the modern internet. Ten years later, two students at Duke University developed a system called Usenet that let them post electronic messages to a neighbouring university over ARPANET: by 1984, 940 host were connected to Usenet … and what was one of the first things they started talking about?

“I was first on the internet in 84. I had access to a college computer lab,” Jonathan Dennis tells me. “It wasn’t even called the internet then. I think at the time it was still being called Arpanet. Average people in their homes were not using this. On my first day, I discovered a Doctor Who group. The big topic of discussion was the hiatus.”

And the internet was born.

To begin with, those early Usenet conversations were pretty primitive: although someone of my generation would recognise the basic principles of posting a message that accumulated replies in threads, things went slowly and it was usual practice to post one day and look for your replies the next. Conversations on the net.drwho group were slow, and because members were limited to those who could get their hands on the equipment, the group was made up of fans all scrabbling to dig up what information there was about Doctor Who to be found.

But, all the same, it served a purpose:

“The initial attraction,” says Jonathan, “was simply finding people who knew what I was talking about. In the USA, Doctor Who is a cult show. Even today, the chances are the person you are talking to has no idea what Doctor Who is. The opportunity to have a face to face talk about it isn’t there.”

That was something that I could sympathise with.

In 1984, it was perfectly fine for me to run around the playground pretending to be the Doctor whilst other kids pretended to be Daleks. I was eight; there was nothing odd about that. After the hiatus, though, things were different: okay, so Doctor Who was still on the telly, but in the minds of the British public it was past its best. The BBC had dealt its iconic status a double death blow by announcing that it was so out of touch it needed to be taken off the air – and then by bringing it back as essentially the same old, same old. By the time Mel Bush bounced her perky way onto the TARDIS, Doctor Who wasn’t a family show any more: it was strictly for the kids, and I stopped mentioning it as something I liked. By the time I was ten, my next-door neighbour could have been Ian Levine and I still wouldn’t have had anybody else to talk to about Doctor Who.

But as Doctor Who slowly slid into cancellation an extended rest whilst the concept was rethought, its fandom was also undergoing a sea-change. As blank videos got cheaper, as Target moved closer to publishing a novelisation of each story, as the BBC helpfully started releasing stories onto video – suddenly it was easier for each fan to investigate their own Who prehistory, and the fans whose status had been earned by virtue of dodgy videotapes – or even dodgier memories – of some of the older stories found that their unique knowledge was becoming commonplace. Even worse, their carefully crafted fan consensus was being eroded by the new fan buzzwords: the memory cheats.

One by one, the big name fans started to fall: Ian Levine – who is either ex continuity advisor to the Who production office and co-writer of Attack of the Cybermen, or a big fat liar depending on who you talk to – found his pronouncements on continuity to be slightly undermined by being proved wrong by some young upstart with a copy of The Sea Devils under his arm; Jean-Marc Lofficier’s programme guides got downgraded from definitive to flawed as the readers started being able to check the facts for themselves; Tomb of the Cybermen turned up alive and well, and found itself regraded from “classic” to “but why did he open the tomb in the first place?”

Suddenly it was no longer enough to just be able to remember what happened in episode three of The Seeds of Death. That kind of trick could be pulled by any dumb kid with a video recorder. To make things worse, there were only so many facts that could be known: the Seventh Doctor and Ace had disappeared muttering a few banal comments about tea, and now we knew that there would only ever be 159 stories to remember things about. All that fandom had on the horizon was endless arguments about whether there were actually only 156 because technically Trial of a Timelord was one story.

As the basic facts grew more commonplace, so the focus went deeper still: this was the age of pedantry and the birth of the still ongoing debate about what the early Hartnell stories should properly be called – but it was also the age of proper, historical research and the unearthing of truly interesting facts about the show’s early years by historians such as Howe, Stammers, Walker and Pixley. And increasingly the place you would go to discuss all of these was online.

In 1987, net.drwho found itself party to the Great Renaming, where a new structure was enforced on Usenet: it became rec.arts.drwho, the then most visible place to go and discuss Doctor Who. As more and more people started to get access to the internet, RADW’s membership grew. Some of the names that started to appear there were already well known in fandom – names like Gary Russell or Craig Hinton, who had both been reviewers for Doctor Who Magazine – but others wouldn’t mean anything to anyone for a good few years. Let’s make it clear: although it’s fairly well known in fandom now that if you visit the Who forums you might find yourself chatting with the someone who wrote your favourite story, that wasn’t the appeal of RADW back then.

When asked, nearly everyone I talked to for this article said that it was the convenience of online discussion that attracted them. There was already a strong fan network growing in the real world, but the internet let them talk to the people they usually only saw at a convention any time they wanted – or just join a growing throng of strangers all discussing the same thing. But that was only part of the appeal, the more acceptable and easily admitted motivation behind the action.

There’s a selfishness, an egotism, to posting on the internet – the same as there is with any kind of writing: the only thing anyone writes solely for the pleasure of someone else is a cheque. All online groups have far more members than they do people posting, and it takes a certain kind of mind to step from reading all the discussions and the flaming and the nonsense and think you’ve got something to add. Mostly, you start with a polite, quiet hello and maybe a question for those wiser heads on the group – but all the same, you’re looking for responses: you’re looking for the members to open their arms and accept you, because you make sense. You say things that are worth saying.

And the gratification can be instant:

“Convenience was one thing,” says Peter Anghelides. “But immediacy was even more appealing. Previously to have a “real-time” discussion with fans, you’d need to be at a convention or the like. Otherwise, there would be exchanges in fanzines that would do over (literally) months what an online thread can do in minutes.”

“I loved the frenetic debating that online fandom offered,” Ian Mond adds. “You’d post something and within seconds there’d be a response. Best of all you’d sit and watch as other people tore each other to shreds over such issues like whether Remembrance of the Daleks was good or a pile of poo and whether Lawrence Miles had destroyed Doctor Who continuity. It seemed all so cutting edge and exciting and vibrant.”

That was why I went online. I’d started writing for DWAS fairly late on, little bits of fiction and opinionated articles about this and that. You’d wait all month for the latest publication to arrive to see if you were in it, and then you’d wait another month hoping that somebody would write a response, an article, a letter, anything. More often than not, they didn’t. When you went online, that whole process took seconds – and when you were completely ignored, you could just chip in with something else and see where that got you.

That’s what gets conversations going on the internet – and what gives any group its natural lifespan. We pretend we get involved in the discussion to learn, to expand, to share … but more often, we assume it will be the people we discuss with who’ll learn something. Three words you rarely see online: “I was wrong”. Positions get entrenched, and arguments are rarely resolved past the “My God I Just Can’t Talk About This Any More!” level. Tempers fray at earlier and earlier stages, leaving the newbies wondering what they said and why no-one wants to talk about UNIT dating any more.

RADW might have been the most visible of Who discussion groups, but at times it wasn’t the nicest place to be – especially for the uninitiated. Kelly Hale’s first online experience wasn’t exactly uncommon:

“I outed myself as a noobie with a question about why more women didn’t write for the New Adventures or Eighth Doctor Adventure book series. I didn’t even know what “flamed” meant, but my first experience with online Who fandom involved me being flamed. I almost didn’t return ever.”

Of course, that’s your normal every day internet: from 1991 onwards, Doctor Who fandom had another issues.

When Virgin started publishing the New Adventures, they developed a pool of fan writers. Peter Darvill-Evans explained years afterwards that first-time authors were cheap and that first-time fan authors were particularly useful because they already knew Who inside out: more than that, though, “They can - and did - talk to each other, co-operate on story lines, and so on”. Some of those fans were already talking to each other on RADW, and some of those that weren’t soon found themselves attracted by the sheer mass of their peers already online.

As they began to chat, the NA authors made friends and enemies. The dialogue was opened up, and could lead straight into the fictional world: is the Ian Mond I’ve been quoting so happily actually a real person, or the computer geek with the interesting skull cap from Kate Orman’s Blue Box?

“Actually, I was disappointed by that,” Ian mock sulks. “I thought there’d be more recognition online. But other than the odd review, no-one seemed to care. I wanted people to stop me in the street and say, ‘hey are you the Mondy who appeared in Blue Box?’”

As the authors used their acknowledgements to thank or berate RADW and peppered their text with fan-name checks, so they advertised online fandom and the glittering prize: if normal online discussion has to contend with people saying anything for a bit of recognition, online fandom has the added problem that more than recognition you might find yourself woven into the very fabric of the universe you love so much if you can just make that author notice you.

On top of this, Who fandom had to contend with the lasting legacy of the NAs: they opened up one of the great schisms in fandom that still hasn’t been repaired. As the books started to bed themselves in, RADW greeted their arrival with a question that had never been asked before but would never go away:

“Who out there considers the New Adventures to be canon ‘Who’?”

At its heart, the canon debate is an argument about ownership. In the most literal sense of the word, a canon is decided by a recognised authority figure, laying down the guidelines against what should be considered core and what apocrypha. Doctor Who has always lacked that kind of authority: it was created by committee for an organisation with convoluted lines of command – should we ask the current producers, or the Director General to define our canon? No, with Who every fan is forced by necessity to form their own canon: the canon debate occurs on the borders, in the disputed territories, of those “personal canons”.

It was the cancellation of the show that gave rise to the question of ownership: campaigning began to bring it back almost immediately, and it developed with a kind of fervour. A certain kind of fan started to emerge, the kind who saw the BBC as a publicly funded body and began to see a causal relationship: if the public paid the wages, then the public should be able to demand a show. It was only fair: they paid for it, so they must own it. When the New Adventures came along, it just made things more muddy: not by their very existence (although that didn’t help) but because of who made them:

“It was … people we already knew – from the online community but also from fanzines and conventions and so on – who became involved in the NAs,” says Justin Richards. “People like Andy lane, Paul Cornell, Gary Russell … Inevitably some of the ‘nouveau professionals’ gained – or were bestowed with – a sort of kudos. But there was – again, in my opinion – a benefit in that a lot of the other fans felt ‘empowered’. They saw their friends or acquaintances moving into professional writing or whatever and that gave them an incentive to try themselves when they might not otherwise have done.”

What is being described is basically the kind of “If he can do it, so can I” thought process that brought people like Kate Orman, Peter Anghelides and Jonathan Blum into the world of Who writing. But there is a flip side to those thoughts: “If I can’t do it, why should they?”

Fandom was already adept at tearing down its old gods, debunking the received wisdom of the ancients in favour of forming their own opinions from direct interaction with the rediscovered texts. Some corners of fandom weren’t about to let new gods ascend in their place, particularly when they were just some fan the same as everyone else but luckier.

“Bad behaviour is present on every Internet forum, including the desire to cut down tall poppies. Even short ones like tie-in scribblers. Hell, even really short ones, like fanfic authors with a few dozen followers. Fandom basically seethes with envy,” Kate Orman tells me, half-serious. “I can remember being told point blank by one big name fan that he wanted to take authors like me down a peg, and I’ve seen similar comments here and there. Seethe seethe, goes fandom.”

In Big Finish’s first year, they drew the attention of one big name fan who took exception to the involvement of Gary Russell and his talk of the business as a small company that needed support from its customers. The big name fan made enquiries with the Inland Revenue and got himself a copy of Big Finish’s first tax return, and proceeded to make noise around the internet about the figures within showing the lie to Russell’s unreasonable, reprehensible claims of smallness.

I know what you’re thinking: boo-hoo, nobody loves the poor author so it must be the fans’ fault. But this isn’t something the authors themselves are immune to: Lawrence Miles spent most of a well-publicised fan interview slagging off his peers and washing their laundry in public because he felt they didn’t deserve the acclaim they were afforded; I started my internet life praising Lance Parkin’s unruffled online manner … and ended it in an e-rant that got out of hand solely because I disliked the unruffled way Lance said I was wrong to question an editorial decision about someone else’s book.

Because nothing about online fandom is straight-forward. For every time some young gun comes to town wanting to try their luck against the old sheriff, there’s some poor innocent stranger getting lynched because the locals don’t like the way he looked at their hero. For everybody who sees the tall poppies and thinks the grass needs mowing, there’s someone planting a “Do Not Walk On The Grass” sign nearby.

“At the time, the books and the audios were seen as the closest thing we’d ever get to proper Doctor Who. And so when the authors started turning up, stating opinions and providing hints and titbits about upcoming books, they were sort of treated like royalty,” remembers Ian Mond. “I remember being very protective of these authors and hating anyone who attacked them.”

If the canon debates that are the hallmark of online Who fandom are about ownership, then it cuts both ways: those that argue against canon very rarely do so as fans of the TV series and nothing else. One of the reasons for RADW’s wariness of the authors isn’t just because some fans see attempts by their peers to usurp “proper” Doctor Who and stamp it with their own limited view of what the show should be. It’s also because sometimes some of those writers did try to use their books to settle old scores: John Peel’s effort to reinstate Skaro were dismissed at length as “a Bad Idea” by Jon Blum on RADW – but Jon himself wasn’t above using Unnatural History to parody his opponents in one of the group’s frequent canon debates, and it was Lance Parkin who took the debate about Remembrance and put it into the mouths of the Doctor and Omega in The Infinity Doctors.

“I got a book commissioned, edited, approved and published by the BBC. I do think, yes, that means I get more of a say than someone that hasn’t done that,” Lance Parkin is saying as I type, in an effort to defuse the latest canon debate. “That’s not to pull rank. It’s certainly not to say that it’s written in stone and can never be contradicted. But it’s there, in a Doctor Who book the BBC published. It’s got to have more weight than if I’d just mentioned it as an idea [online].”

What you can see in the canon debates – in most of the early discussions in online fandom – is the battle lines being drawn up over whose ideas get to be part of the tapestry of Doctor Who. It’s something that came to Who only with the advent of the NAs because it is – at its heart – a fan obsession: when Doctor Who was on the TV, the production team were only interested in making a good 25 minutes of TV every week. The idea of them looking back to the show’s past at the contradictions and the mistakes and trying to solve them … on the whole, it wasn’t something they considered. But fandom, fandom had been arguing the “true” meaning of the pre-Hartnell faces in The Brain of Morbius since it was broadcast. With the advent of the NAs, however, suddenly the producers were also fans: they had the perfect storm of an inclination to theorise explanations for continuity issues and the ability to introduce those answers into the fictional universe.

Before, you could easily dismiss another fan’s theories … but then books like Timewyrm: Revelation, Cat’s Cradle: Time’s Crucible, Lungbarrow, The Infinity Doctors came along and made those theories facts. Those that liked the explanations could get behind them one hundred percent, but those that didn’t … Almost immediately, these divisions became entrenched, and the very nature of online discussion – the need for the gate to squeak loudly and dramatically to get the attention it wants – quickly led to confrontations and flared tempers. But prior to BBC Books authors Blum and Peel having their big bust up over Antalin, the authors didn’t let their tempers flare. In the NA days, everything was a lot more gentile and controlled.

“Jesus - there were loads of arguments!” Gary Russell is quick to correct me. “Some of us automatically chose not to air them in public but there certainly were as many spats as there were during the BBC Books days.”

As with any golden age, there’s a tendency to look back at the New Adventures as being something elementally different to what came after. Their editor was a full time professional, not a “freelance consultant”; their arcs were planned, discussed and executed; their authors were all singing from the same hymn sheet, and when they weren’t somebody would have a quiet word and make sure that nothing ever made it to the fans ears.

“I don’t remember ever being told by Virgin not to comment on the other authors,” Kate Orman recollects, and Justin Richards agrees: “As far as I know there was no direct ‘order’ that we shouldn’t fall out or criticise. Yes there are one or two who are a bit outspoken. But that’s just the way they are.”

The truth is, the differences between the NAs and the BBC Books are fairly cosmetic: at the end of the day, they were being made by and large by the same people, for the same people, in the same way. Arguments between authors happened then as now, with the only difference being time has made the earlier arguments fade a little in the memory: any argument is only ever relevant in the moment, and once that moment has passed they’re soon brushed over.

“My back-and-forth with John Peel ended months before I got published,” Jon Blum remember, “just like John’s comments about Daniel O’Mahony, Ben Aaronovitch, Craig Hinton and so forth were before the Beeb picked up War of the Daleks.”

What made some inter-author arguments stick in the mind – sometimes long enough for past arguments to be redesignated inter-author when a fan got lucky – wasn’t that they were rare, or even that they were out of step with the discussions going on around them: it’s that fans and authors alike share the same vague unease about those writing Who having an opinion on it. Peter Anghelides explains:

“Before I got published, I would post online reviews — including some quite assertive ones where I didn’t like something. But now, writing new reviews is a lose-lose for me. On the one hand, if I post a positive review then the cynical reader will say I’m just being kind to my friends and potential employers. On the other hand, a negative review gets picked up and spun as a “fight” with my friends. And on the third Venusian hand, a review that makes no assessment isn’t really worth writing. (I stole that Venusian hand gag from my friend Andy Lane. Have I mentioned how brilliant his books are?)”

The cynical reader will notice how kind Peter is being there to his friend.

As a Doctor Who writer, there’s always the urge to not say much about what you think of how your peers are doing. Partly there’s the knowledge that any genuine comments are going to be misinterpreted one way or another. Partly, there’s always the fear that you will kill the golden goose and say something so unsayable you’ll never be asked back again: you’ll suddenly become an ex-writer of Doctor Who. If it was any more so in the early days of RADW, then it was only because everybody was new at this back then, and they hadn’t the experience to know that none of it really mattered: at the end of the day, if Lawrence Miles got The Adventuress of Henrietta Street and The Adolescence of Time commissioned, then Doctor Who truly doesn’t hold grudges. Or perhaps it’s a generational thing: the NA authors were from the 1st wave of online fans, those that had memories of meeting fans face-to-face; the next wave, however, didn’t always have those experiences – to me, the majority of the fans I’ve talked to are just words on a screen, and it’s much easier to find yourself treating it all like an early BBC Micro adventure where the only consequence of foul language and grumpiness is a syntax error.

But whether the authors pulled their punches or not, those discussions were out there. They were the lifeblood of RADW – just as, increasingly, any arguments were. As with any online group, it moved slowly into the phase where the overall pattern of a discussion was already well known – could even be anticipated by jumping straight to the punch line of “McCoy SUX!” or “It Ain’t CANON!” and sitting back to enjoy the oil your squeaking had earned you.

The thing was, Usenet was truly democratic: it had no owners, and – away from the .mod suffix – no moderators, no one authority figure that could step in when things got out of hand. After a while, this was seen as The Problem with online fandom. What was needed was something that was less of a free-for-all, something more structured. Kate Orman was one of the leading figures behind attempts to get a moderated version of RADW off the ground, rec.arts.drwho.moderated.

“The better moderated the forum is, the less bullying, abuse, ridiculous spats, and attention-seeking idiocy get through to embarrass us all,” she explains. “Unfortunately it took me so long to get my finger out and get the newsgroup created that alternative venues were already beginning to provide relief from the free-for-all.”

One of those “alternative venues” was the eGroups list Jade Pagoda, established as a place to discuss the books and only the books in an era when the idea that there would be a TV show to discuss was becoming an increasingly marginal view. The list was extremely popular, and at its height was the third most populated list on eGroups’ successor Yahoo!’s books. Like RADW, the list was available for any fan to join and immediately start chatting on. But JP had something different to RADW too: rules.

With a safety net of moderation in place, and strictly enforced rules that marked general chat about the TV series off-topic, JP started to attract a number of fans and authors. JP painted itself very much as the home of the discerning book reader, a friendly more inclusive place than RADW where a canon debate would never raise its ugly head, because it was populated exclusively by people who read and enjoyed the books. Not by people who wanted a good reason to ignore them.

But it wasn’t friendly to all authors: JP placed itself very firmly at the “rad” end of the scale, deifying authors like Miles, Parkin and Cornell whilst demonising the Russells, the Bulises – and, to some extent, the Richardses. But that was alright, because with the advent of the Big Finish audios the trad end of the scale got their adoration and dedicated discussion sites, with their “like-it-used-to-be” writing credentials boosted by actors who used to be on the TV show that the writing tried to be like. With the TV series gone, fandom took these new continuations to their hearts – and the people who made them.

“For 16 years, Doctor Who was very much a fan property,” thinks Ian Mond. “It was the author who guided the off screen adventures, giving life to a number of additions to Who mythology – like Looms and the Other and the Doctor having a belly button, or something. And it was the author who kept Doctor Who’s hearts beating when the rest of the public had thought the show was dead.”

Whether it knew it or not, fandom was going through its first real golden age: the TV show that they loved might not be being made any more, but whatever their taste, somebody was producing merchandise to satisfy it. Explorations of various aspects of the original show, both academic and humorous, were produced in their droves; fans wanting new stories of old Doctors had them in prose, audio or comic strip; fans wanting new adventures pushing the show’s history into the future were likewise satisfied. The post-TV series landscape even managed to throw off a number of spin-off series – something the show itself had tried to do on more than one occasion, and failed.

“The problem for the twenty-first-century Doctor Who fan is not so much philosophical and logistic. Doctor Who in the last five years has become what might be described as super-fragmented … Even a rich fan with a great deal of time on his hands would have trouble keeping up with every release, let alone assimilating and enjoying them all.”

And discussing that ongoing Doctor Who story with a large number of like-minded individuals had never been easier, thanks to the internet. And, conversely, had never been more difficult: as Doctor Who diversified, so online fandom splintered. It was inevitable and even understandable that factions arose, simply because fans lacked the common ground for discussion: if you wanted to talk about the Doctor’s most recent adventure, would you be talking about a Big Finish audio, a BBC Book, a Telos novella, a comic or even a BBC Cult podcast? If you didn’t know all five, how long would the conversation last? Even when it gained a new place to air its differences, with the 2001 launch of Outpost Gallifrey’s forum, fandom still had to be separated into its little cliques and corners to allow for common ground and shared experience: Gary Russell was a very active poster throughout my time on OG, but I don’t think I ever read or responded to any of his posts simply because he stayed in the Big Finish forum and I frequented the Books. Over there he was a hero; over here a villain.

The success of OG gave the illusion of us all being fans together, all coming together in one place to celebrate Doctor Who and the many diverse delights it had given birth to. But the truth was fandom was fractured, rife with petty fiefdoms and rivalries being played out again and again.

“There will always be rivalries and personal preferences in any group of people who are fans of any particular endeavour – whether it’s Doctor Who or stamp collecting or crown green bowling,” thinks Peter Anghelides. “Old Series, New Series, Books, Audios, specific writers … they’ll find something to disagree about because (a) that’s the fun of online discussion and (b) people want to be experts in some field and it’s a kind of control for them.”

But even against this background of old grudges and fights for control, the internet was giving the fans a voice and an access that was having great positive effects. For the first time in the show’s history, the people making new Doctor Who of whatever flavour were there talking to fans twenty-four hours a day. They couldn’t help but be influenced by the discussions they were having: sometimes, that influence went too far and the spin-offs could seem like they were little more than a final thumbed nose to win an online argument. But when it worked … it gave a depth to the work, a injection of communal thought that informed the books and the plays and made them connect with their audiences like never before.

When Faction Paradox and the impending war were first introduced to the BBC line, they caught the imagination of the readers and the writers in equal measure. Everybody got involved in the discussion, building a much more comprehensive picture of the possibilities and the pitfalls than any one author on their own would have been able: the future enemy became The Enemy, and the War went from unimaginably far off to looming over the space of a few books because the readers had been able to tell the authors they wanted to know more. The closeness between fan and writer even managed to have benefits in the real world, with a spate of unofficial anthologies with stories written by the people making official Doctor Who providing the draw to raise substantial amounts of money for charity.

It’s probable that such a position wasn’t sustainable: although things are always worse now than they were in the golden past for online commentators, as 2005 approached there was a general feeling that the spin-off ranges were winding down. Telos lost their licence to produce Who novellas, BBV imploded and BBC Books halved their production from two to one Doctor Who book every month: sales had, for one reason or another, been hit to the point where seven years after publication, Heritage still hasn’t come close to covering its advance. Other factors undoubtedly had a part to play in it, but in fandom doubts about the future started to appear.

For years, fans of the New Adventures had been saying that only one man was in any position to save Doctor Who. Only one man was held in high enough regard in television to be trusted to bring back a sixteen year dead TV show, but also had the necessary “rad” qualifications to do it properly. It’s interesting to note that in all these discussions resting the future of Doctor Who on Russell “Television” Davies’ shoulders, the majority of book fans were hoping for a televised version of the New Adventures: dark, adult and for a niche audience. No-one imagined that Doctor Who could ever be the success it had been before – the best they could hope for was that it would briefly flower again, and validate their loyalty to the books by being as much like them as the medium would allow.

To hear them talk now, it seems like they’d always thought it inevitable that Doctor Who would succeed, smashing records and resurrecting family television in its wake. But Russell T Davies wasn’t the saviour the books fans had prayed for: as with the ascension of Christopher Eccleston in The Second Coming, the arrival of something that seemed to reaffirm the power and the importance of the old guard instead led to the sweeping away of everything that had gone before, and the rise of a new order.

“In the early days,” Jon Blum remembers, “the novel writers were up among the gods just like the show writers. It was just as much of a visitation when Paul Cornell or Andy Lane dropped in on RADW as when Johnny Byrne or Chris Bidmead did.”

“But it really is amazing how the shape of online fandom has changed in just six or so years,” Ian Mond interjects. “Unless they’ve written an episode of the TV series, the so called big name fan authors are no longer as relevant as they once were. They’re now ordinary fans, no longer privy to the inside running of what happens in Cardiff. I think for some of the authors it’s been a bit of a bitter pill to swallow. And not all of them have coped.”

When Lawrence Miles did his interview laying out his feelings about the books, their editors and his fellow writers, it was seen as an important event. Whichever side the people who read it came down on, there was no particular backlash or feeling that he had overstepped the mark: he was someone involved in the making of Doctor Who expressing his views on it, like Eric Saward had expressed his views about John Nathan-Turner. When he posted his infamous blog review of The Unquiet Dead, the outraged responses he got caused him to twice re-write it and then remove the whole thing in favour of a self-diagnosis of mental illness. The tide had turned, and now Miles is lucky if his blog even provokes enough interest to raise it above the mass of other fans unconnected to the show with extreme opinions to share.

But it’s not just the writers that have had to adjust: suddenly the fans have found themselves in the same position. Where they used to have a direct line to the people making new Who, now they’ve suffered a shocking return to the pre-1990s status quo: a distant production team only listening to fandom as one of a number of responses. Suddenly Doctor Who isn’t being made with them in mind: it’s courting a much larger, wildly different audience … and finding it.

You’d think that would sound the death knell for the old divisions and animosities: as the old guard, the books vs. audios vs. classic series camps would join together as one and engage with the new show, either as the much awaited return of something they loved or as an impostor masquerading as Who by dressing itself in its clothes. But, as Jon Blum puts it:

“Never underestimate fans’ ability to hold a grudge. There are still people cursing the name of Richard Briers twenty-odd years after he had a bit of a lark in Paradise Towers.”

In many ways, the old divisions still remain, and the canon debate continues. Online, the old guard struggle to acclimatise to this new reality: some have turned away from New Who in disgust, whilst others have jumped from the spin-offs to the TV series as easily as they jumped the other way in the ’90s. Some claim the involvement of Paul Cornell and the reworking of Human Nature as proof positive that the NAs had it right all along; others point at Rob Shearman and the adaptation of Jubilee to say the same about Big Finish. But now there is a new division to contend with, and it expresses through the language used to discuss it: did Christopher Eccleston play the Doctor in the first series of Doctor Who, or the twenty-seventh?

This debate expresses many of the concerns of the old guard: first and foremost, it is concerned with the minutia of the production whilst being ultimately pointless, as all good fan debates should be. More importantly, what it is being asked is whether this new iteration of Doctor Who is the same as the previous one, or if it – and, by extension, any other form of Doctor Who created at a one step remove from the original series – is something new, something different, something of its own that can be mentioned in the apocrypha but doesn’t have a bearing on the one true history? It is, at its heart, a canon debate.

Whilst the debates being carried out are reassuringly familiar, the internet that they are being carried out on has changed remarkably. The most obvious change is the sheer volume of people who are there now: we are now seeing the third generation of internet users flooding online, people who weren’t even born when the last episode of the classic series was broadcast but who were brought up with HTML as a second language. Their very presence, their sheer volume, pushes these debates out onto the fringes: the Outpost Gallifrey forums are still one of the number one places to go to discuss Doctor Who, but now the overwhelming bulk of people only visit the new series areas. The debate has moved on to who should be the next Doctor, the next companion – and they are being carried out very much in the public eye.

If Outpost Gallifrey is the first port of call for fans wanting to discuss Who, it’s also the first place a journalist will go when he wants to find out “what the fans think”. When it was announced that Christopher Eccleston was leaving Doctor Who, OG’s forums went into meltdown with people criticising him for dealing a death blow to the show so soon after its resurrection: things got so heated that the forums were shut down to give the worst offenders time to consider their actions. The next day, this was reported in national newspapers across the UK. Suddenly it became clear that whilst the fans no longer had a direct line of contact with the makers of Doctor Who, they still had a very powerful new way of having their voice heard. If you made your point loud enough, extremely enough, then you might see your avatar’s name in your daily paper and have however many thousands of people think that you are the voice of the fans, even if for only a day.

But something else this influx of new fans has caused is a mass migration to Web 2.0 platforms. Jade Pagoda used to be the beating heart of Doctor Who book fandom, but now it languishes with barely one post a week as the type of books being produced moves further and further from their “rad” bleeding edge ideal. Now Facebook and Live Journal are taking over as the natural homes of Doctor Who fandom: Doctor Who boasts 178,000 “fans” on Facebook, and its discussion group has nearly 20,000 members. As WYSIWYG editors become more prevalent on the internet, so the discussion of Who moves away from communal forums and onto individual blogs and websites: the bleeding edge of fan thought is now carved out in comment boxes and status updates.

But that said, the way fandom uses the internet now hasn’t changed all that much from the very early days. If Jonathan Dennis had accidentally connected to the Live Journal of 2009 instead of the net.drwho of 1984, he’d still recognise the basic process of watching the show, posting a comment and having somebody else post their response later. The world of Web 2.0 is supposed to be a revolution, but the revolution hasn’t happened yet: instead, we’ve got the same people offering the same services but on newer, prettier platforms.

Far from being a process of increasing freedom, of creative control over the internet and the programme, what online Doctor Who fandom has seen instead is a gradual process of restriction. In those early days, RADW was open to anyone to say anything: that was its appeal, and that was its main flaw. The solution was to move to internet forums, to lay down rules and appoint moderators, but even then the undesirable post, the blatant trolling, still managed to creep through. Now, the online fan is moving away from the forum and taking ownership of their discussions: they post on their blogs, their social networking pages, and they have the final say over who gets to read, who gets to engage and who gets left out. Every fan is now their own moderator.

“I watched a number of discussions on Live Journal about whether the Doctor’s rejection of Martha at the end of Series Three was a form of ‘accidental racism’ from a safe distance,” Ian Mond tells me. “There was plenty I wanted to say on the issue, and if it had been the days of rec.arts.drwho, I might have stuck my oar in. But in the LJ climate, where one comment can be completely taken out of context and then linked to 100 other LJ’s were people will call you a racist a bigot and a Rose shipper, I thought it was better if I kept quiet. And I admit that that’s cowardice on my part. But I think when someone’s perception of you can be twisted by a three sentence comment on a LJ post … well, it’s just not worth having the debate in the first place.”

Despite the influx of new blood, fandom is still fandom, it would seem.

Despite all the promises of Web 2.0, what it comes down to is different ways of doing the same thing: people remain people, and regardless of the technology they will want to do the things that people want to do. Web 2.0 has changed nothing, it has failed: it is worthless.

Except …

What the internet has always shown us is that its impact can be massive, and that it will revolutionise things in ways that nobody really predicted. Something that was meant to protect the US military in the event of a missile strike has instead been used to make shopping easier, the make friends around the globe, to share information, to entertain, and to bring music and film makers to the brink of financial ruin. Web 2.0 hasn’t failed – it hasn’t even started yet: what we’re seeing at the moment is the old wave trying to adapt what they’ve always done to the new models. The new technologies have provided the opportunity for greater interaction, great control, greater ownership … but so far that killer application that utilises that potential to change our lives hasn’t arrived.

If you want the model of the future of Web 2.0 in Doctor Who terms, you shouldn’t look at Facebook: you should look at the BBC website’s comic creator. From a collection of stock graphics, Doctor Who fans of any age go online and create their own stories, engage in their own personal version of Doctor Who, through technology that takes the difficulty of creation out of the equation. Perhaps the finished products have no intrinsic value to anyone other than their creators, but the connection they feel to it is so much stronger than to anyone else’s version of what Doctor Who should be.

It’s the fan fiction of the future.

It’s what the TV series will be in twenty years.

This is what we’ve been promised ever since interactivity found its way onto entertainment’s radar. Imagine sitting down to watch Doctor Who and filling in a form first, or having your programme defined by a set of pre-existing preferences. Did you enjoy Paul Cornell’s last episode, or Mark Gatiss’, or both? Tick this box for an adaptation of Nightshade as scripted by our Cornellbot. Ever described the companion as pouty, planky or shouty? Tick here to choose your preferred identification character, or upload a photo to be digitally inserted into the story yourself. If you thought it was good when the TV put Human Nature up on the screen, imagine how you’ll feel about The Spaceship Graveyard. Or how about a version of Time Crash with Sylvester McCoy returning to his popular role as narrator of What’s Your Story?

That’s the dream or TV executives everywhere … and fandom’s nightmare. You thought fandom was fractured by the lack of a shared experience between fans of the NAs and Big Finish? Imagine how bad it’s going to get if you can sit down to watch the same programme as the rest of OG and still not have a shared experience. Imagine trying to fit that into your carefully compiled online timeline of the Whoniverse.

Enjoy today’s canon debate, my friends. It may be your last.