Invitation

At the beginning of February 2014, I’d just finished a first draft of an as-yet-unannounced novel for Obverse but already knew it needed another run at it before I could call it finished. Since it’s been something like two years since Stuart Douglas at Obverse first asked me to pitch him something, I thought I’d better get in touch and check he didn’t need to see it urgently. He didn’t - which was fortunate, as I was just about to put it to one side to write my story for Iris Wildthyme of Mars. When I mentioned this to Stuart, it must have set a few braincells firing: he asked if I had any desire to edit an Iris book of my own. Although I quite regularly beta-read other writers’ work, I’ve never actually edited anybody else. The idea was appealing, not least because it would give me the chance to say I had editorial experience. You never know exactly what might lift you up above the crowd …

We discussed terms, and I promised to come back to him with an idea as soon as I could.

Inspiration

The first idea I had for an Iris collection involved Iris getting pregnant. The trope of the mystic pregnancy was very much on my mind after Amy Pond’s storyline in Series 6 of Doctor Who. I’d been disappointed by the way having a pregnant lead and her family in an action adventure show had been treated as problems that needed a dramatic solution, rather than just things that real characters did. I knew that Iris was a particularly good canvas for dissecting tropes, and knew she wouldn’t let anybody tell her she couldn’t have adventures because she was growing a baby. I had the idea of a collection that showed Iris’ relationship with her child, from the conception (with the father a new companion created for the book), through an acrimonious bid for independence and then an after-death reconciliation in Philip Purser-Hallard’s City of the Saved. I also mapped out a vague plan for the father’s life, starting as a reluctant companion before breaking free of Iris to settle down without being able to completely let her go.

I pitched the idea to Stuart, but he didn’t think it was quite right for Iris or her audience. I had to rethink.

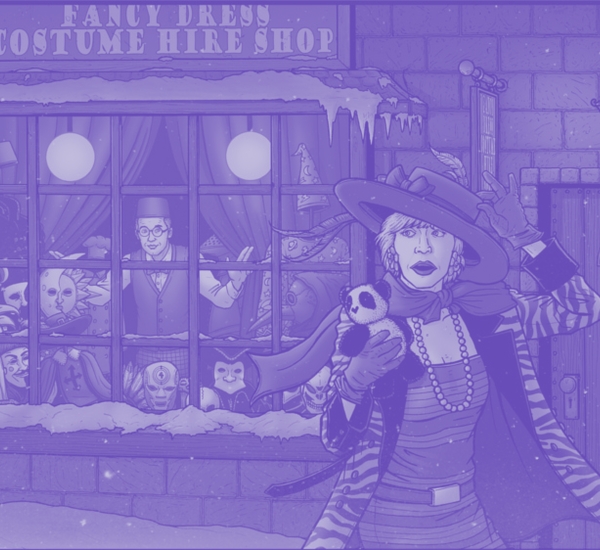

Around the same time, I’d started getting ideas together for another story that came to me as the question “What if Mr Benn was just delusional?”. The story wasn’t quite formed, but I knew it would have a version of Mr Benn’s fancy dress shop in it. The two ideas started to bump together, and suddenly Iris and her new reluctant companion were in Mr Benn. She seemed to fit. Then the idea of where exactly the fancy dress shop had come from came to me.

The Pitch

I got back in touch with Stuart a few days later with a couple of paragraphs describing the new story as I saw it. I suggested the idea of the book being built like a series of Doctor Who, with me playing the role of producer. My idea was to plot the book around the stories that people pitched to me, asking them to include the odd snippet here and there to keep the overall story running along. I also worked up a vague idea of an antagonist for the meta-story: it was little more than an Iris-y sounding name - the Weevil from the Dawn of Time - but I figured that it would become clearer as the story developed.

Around October 2014, Stuart got back in touch to give the collection the green light.

All that I needed now was a story.

Getting the Story

The first thing I did was write up a pitch document, which gave some details about the main characters: Iris, Panda, the Shopkeeper and of course the village of Samhain where the fancy dress shop resided.

Physically, I based Samhain on Heptonstall in West Yorkshire: I’d visited the village years previously and knew it was just waiting for a Doctor Who story to be set there. I dotted out a few vague ideas for Samhain’s history: Heptonstall had some interesting Civil War history, so I chose that period for the founding of the village. I knew I wanted to have an explosive climax to the book, so gave some details about when the village was destroyed.

I liked the pitch document. If I don’t find a spark of inspiration from a pitch document, it takes a lot to drag one out of the ether, and the work probably suffers as a result.

I also had plans to have Iris discover the history of Samhain out of order, so invented a post-destruction period for her to visit and look back from. The intention was to borrow the structure of my fan-fiction Back From the Dead, where the Doctor visits a village recovering from a disaster that he then goes on to create in the next story.

I was certain that I wanted a completely open submission policy. It’s become the tradition with the Iris collections for one story in any collection to be chosen from unsolicited submissions, and then invite submissions for the others from people the editor already knows. That way Obverse can support new voices, but also minimise the potential risk of someone untried failing to submit and leaving a big hole in the book. But I knew that my book wouldn’t be out for at least a year, and I hoped that if I set the deadline for submissions fairly early, I would have enough time to deal with any disasters. To that end, I planned on filling all the slots with other people’s stories: if someone didn’t deliver, I could plug the gap with my story about Iris meeting her companion again in the City of the Saved. Otherwise, I could concentrate my efforts on editing.

The only down side of choosing to do it that way was that I had no idea if I would get any submissions at all. I arranged for Stuart to put the pitch document on the Obverse website and waited to see if anybody would bite.

Why would you not? As an author of many years, writing is worthless if nobody ever reads it. Any chance to see my words enter the public domain is a chance I could not turn down. An opportunity is only an opportunity if you take it, otherwise it just festers and becomes a regret.

One by one, other people decided to give pitching a go.

Funnily enough, my decision to pitch a story in the first place was mainly to encourage other people to do so. ‘It’s easy — look, I’ll show you!’ Then after I pitched it, of course, I got incredibly invested and nervous.

One part of it is Obverse loyalty. The books are filled with interesting writers that I’m always happy to shoehorn my way alongside, assuming I’m not busy with another project during the submission window. Hearing that Dale was going to be the editor, I was intrigued, as I’ve always liked his aesthetic as an author, and was interested in seeing how that would translate into a curated collection.

I like writing Iris, and I had an idea, and — well, at that point you might as well just get on with pitching, right?

Slowly, piece by piece, I got enough stories to build a collection around.

I was - I have to admit - surprised at how many of the pitches I got could’ve gone into the final collection. Only one person tried pitching me their novel instead - addressed to a Mr Sam Hain to show they really hadn’t bothered reading the pitch document - and there was only one that I couldn’t see working at all. More surprisingly, I had more submissions than I needed - even being optimistic, I’d assumed that I would have to accept everything workable I had to make up the word count. Instead, I had the luxury of choosing those stories that brought something to the overall collection.

I started dividing the stories into groups: I needed some that could introduce Samhain and the Shopkeeper, some that could be adapted to include the plot points I needed for the meta-story, one that could include the destruction of Samhain and the climax of the story, and then others that could fill in the gaps. It was in the gap-fillers that I looked for the ones to reject: where there were two that were similar in tone, or in action or just in the place they would fit into the collection, I made the decision to accept the ones that came from unpublished writers. Where it was a head-to-head against two unpublished writers, I chose the one that felt most like something I hadn’t seen before.

Very quickly, I had the overall shape of the book. Those that I was rejecting got some feedback about why and - contrary to my own fears - took the decision graciously and professionally. Then I settled down to start the actual editorial.

Editorial

The first story I accepted was the first story in the collection. It was the only real choice for the slot, being a cracking and very Iris tale that managed to set up both the premise and the village at the same time. It was written by someone I usually interacted with as my editor: Jay Eales.

I made my pitch quite close to the deadline, and misread the guidelines asking for a couple of paragraphs, and sent a couple of pages. I guess to some extent, the longer pitch I sent gave Dale a better idea of what I was proposing to write than a quick couple of paragraphs could have managed. I apologised as I sent it, hoping that Dale would read it anyway. As I recall, the reply came back a couple of days before Christmas, with Dale saying that not only would he not accept my apology, but that he wanted Death of the Author as the first story in the book. Oh, and asking to borrow one of my supporting characters to use in later stories. Nice Christmas present!

I waited to hear back from Jay before I contacted any of the other writers I’d chosen, so that I could let the others know that a robot Tom Jones was available to use in their stories if they thought it would fit. As everyone had only submitted pitches - not finished stories - I wanted to feed them their plot points before they started writing. For the most part, that just meant telling people about Tom and letting them know what had just happened in Samhain when their story started. Some got more: Juliet Kemp got one of the major plot points to include in her story, which rather surprised me as I’d assumed that what I wanted to happen was so specific I’d have to write that story myself.

When I read Juliet’s pitch, not only did it dovetail nicely with Kara Dennison’s story but I could see my plot point would slide in neatly without disturbing what she wanted to write at all. That was the point when I decided I would do my best to build the meta-story out of what I already had, rather than ask the writers to amend what they were doing to crowbar it in. The Weevil from the Dawn of Time was jettisoned, and instead one of the characters from another story got elevated to antagonist. The idea of having Iris experience the collection out of chronological order also fell back a little: it’s still there, but not as highlighted as I’d intended to have it. The stories would have needed too much fiddling to get it to work.

With everyone briefed, I set them a deadline that would leave me enough time to step in if I needed to, and went off to enjoy Christmas. The writers weren’t so lucky.

I’m currently in a writing program so I write often and I’ve even managed a few small publications. So I figured this wouldn’t be too hard. I was wrong. The fact that the story revolved around atmosphere and the town instead of a plot with twists and turns meant that if I didn’t pull off any eerie moments there was nothing to fall back on. So I kept going over and over some scenes, especially the one in the church, hoping that it’d be effective enough to give the reader chills. The process ended up making me a stronger writer, difficult as it was.

The stories started to come in, and it was time to find out what kind of an editor I was.

Once that Mr. Smith untied me from the chair and stopped burning my feet with cigarettes, I found [the editorial process] rather splendid. Dale is very easy to work with and was encouraging throughout the process. Outside of a clarification regarding a date in the story and a few specific “arc” elements Dale wanted me to add, little was changed.

Where I could, I tried not to stick my oar in too much. I had several writers who knew more about what they were doing than I did, and on the whole the stories worked so well all I’d be doing was making them more like I’d written them. I don’t know if maybe some of the writers expected a little more feedback though: it can be disconcerting as a writer to have someone tell you your story is perfect and doesn’t need anything doing to it. But in some cases, the stories were perfect and didn’t need anything doing to them.

I like having someone edit my work. There’s always something that can be improved, and a thoughtful editor is a gift. (Even when you disagree with them…). On this occasion I think there was very little editing done, but that is of course reassuring in itself.

What I tried to do in each case was tell the writer what my initial response to the story had been: whether I’d laughed at certain bits, or found other bits a little confusing, and what I thought was happening at the key moments. A lot of the writers in the book were writing their first published stories, and I knew from my own experience that sometimes the most useful thing is to find out what somebody else thinks your story is doing. We all carry a version of our stories in our heads, and without a bit of distance that version can blind you to the words that are actually on the page.

I’ve never worked with an editor before and was unsure as to what to expect or whether my work would live up to their expectations. I found the feedback I was given really useful, forcing me to think about my story in new ways and spurring me on to make what I think were big improvements to it. I’m not sure if I made the most of having an editor looking at my writing, as, to be honest, I wasn’t sure how much I should contact them or elicit feedback. But the feedback I got was very useful and I would be keen to write in a similar set-up again in the future.

You’ve a knack for identifying all the bits that I thought I’d written but didn’t, all the transitions that needed to be there, all the places where I was being a bit too clever for my own good…

Outside Help

Everybody needs a little outside help with a story if it’s going to work. Every writer has their own people that they go to for a first opinion, people that they trust to tell them honestly what they think.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the members of the Speculators writing group in Leicester, who were my first readers, and helped me to hone the first draft of my story before I sent it to Dale, which may have given him less of the easy targets to spot.

One of my go to people is Ian Potter.

I decided to pitch because I was interested in working with Dale, whose writing I’ve always enjoyed. We seem to have similar tastes and interests and have alarmingly parallel CVs, so I’d hoped we’d end up with a collaboration where we ended up pulling each other to interesting places we wouldn’t quite have ended up alone, rather than one where we ended up pulling each other apart. It helped that I greatly enjoy working for Obverse and with the character of Iris Wildthyme.

I didn’t think I had an idea for the collection, so I followed the advice of veteran TV writer Dennis Spooner who reckoned you should look for your story in a TV series where you think there might be a problem with the series format, and pondered what I might do that I thought no one else would.

That led me to thinking about a story which wasn’t about Iris dressing up in the shop and having an adventure like Mr Benn and pondering what kind of fictional entities might particularly prey on, and play in Samhain that no one else would have used.

When I received Ian’s pitch, I realised that it had at its heart an idea grand enough to be the climax of the collection. He’d suggested a story set predominantly in the early days of Samhain, and built on some of the history I’d only vaguely hinted at. And it introduced a character called Michael Drake, who had a pivotal role in the history of the village. I’d had a vague idea that I would probably be the one to write the climax story, but to be honest I was reluctant because I didn’t think it would play to my strengths. I was also still vaguely toying with the idea of writing my City of the Saved story for the collection, if I needed to write anything.

So instead, I talked to Ian about the things the climax story would have to wrap up from the meta-story and asked him whether he’d be willing to give it a go. In turn, his “fictional entities” and their influence on Samhain got woven into the other writers’ stories and became the antagonists of the meta-story.

I was over-committed with other things while writing the story which meant it came very slowly, and Dale was hugely supportive and understanding through that, giving me ridiculous amounts of time to get the story drafted.

By the time I received his first draft, I’d had all the other stories in. I had a rough draft of the whole collection, and I realised I’d made a mistake. When Stuart Douglas had first talked about the book, he’d talked about it being 60,000 words. When he confirmed that it was going ahead, the word count had been upped to 80,000 words. But I’d done all my calculations based on the original figure, and hadn’t thought to update them. I was 20,000 words short before I’d even commissioned the first story. Fortunately, I’d already snuck one more writer in than I’d originally intended, and some of the other stories had come in needing more words than I’d originally allocated. The deficit wasn’t quite so foreboding, but I was still going to be short by about the length of one story.

Dale had given me a short ‘shopping list’ of things that needed to happen to serve the larger collection, but I found, as I wrote the story, that it was growing way beyond the expected word count to get them all in. I also found I wanted to rework the planned ending!

The story ended up spending a lot more time in the modern era than Ian had initially planned, and that had eaten up his word count. The way he accommodated that was to only sketch in some of the 1643 backstory, so that they felt more like back references to a story we hadn’t read. As one of the things the backstory was setting up was the nature of his antagonists, it robbed his ending of some of the power it could have had. And in the back of my head, I knew that I was probably going to have to write a story to fill in the shortfall in the collection’s word count.

I suggested that we split Ian’s pitched story in half: what he’d written already would form the second half at the climax of the book, and all the bits of backstory that hadn’t quite fitted in would form the first half. This story I would write, and it would appear before Ian’s story so that the antagonists were already well established before they showed up again to be defeated. Ian agreed, and so we went our separate ways to work on our halves.

I felt like I’d got the easy end of the bargain: most of the things my story needed to do were already there as callbacks in Ian’s. Most of what I needed to turn those plot points into a story he’d already suggested: the nature of the beast, the setting, most of the characters and even the climax of my story. All I had to do was something I’m always good at: take somebody else’s established facts and then run with them to somewhere else.

I finished my first draft shortly after Ian finished his second, and I gave him what I’d written so he could make sure it all fitted in with what he needed. And also so he could complain if I’d broken his ideas. He was - thankfully - incredibly flattered at the idea of a story written out of off-the-cuff remarks and reinterpretations of scenes he’d already written. We agreed that he would get a credit on the story - since it wouldn’t have been possible without him - and the two stories were slotted into their respective places.

The Perennial Miss Wildthyme was finished.

What Happened Next

With the words on the page, we were pretty much ready to go. Paul Hanley had already done us a customarily gorgeous cover featuring Iris, the shopkeeper and his shop based on a description I’d given him before any of the stories had been commissioned. My pen name had caused confusion again, and so The Perennial Miss Wildthyme joined What Guns Do and Flywheel Revolution in the “things accidentally published under my full name” gang.

We were due to see the first copies of the book just a couple of weeks after I sent the final draft across to Obverse, but life intervened. The company who were printing the books went into receivership, which effectively meant that Obverse were unlikely to see either the books or the money they’d paid for them ever again. Stuart Douglas spent a hectic few days trying to find an alternative, and then one morning - as if by magic - a copy of The Perennial Miss Wildthyme appeared in my letterbox.

It’s still early days for the collection, and as yet we’ve seen no reviews for it: the Iris books don’t always get many so it’s possible we won’t see any at all. But I’m incredibly proud of the book that me and my collaborators have put together, and I hope that at least some of you get to read it.