Motivation

In 1999, I spent a year studying a post-graduate diploma in Writing for Theatre at Manchester University, and living with three friends I had made on my degree course. The writing course wasn’t very good – it consisted of a placement as a runner in the light entertainment team at the BBC and retaking the writing module I’d done in the third year of my degree. I didn’t particularly engage with the course either, though: it was bursary funded, so it gave me a year to learn whatever I wanted to about writing, but instead I spent the year writing some plays the same way I had always written them. I did, however, complain about the BBC placement: after pointing out that light entertainment didn’t do theatre and also didn’t use scripts, I made my tutor aware of the Royal Exchange Theatre’s First Eleven writers’ group and bullied him into making attending it my diploma’s placement segment.

What I did with the time I didn’t use finding out about structure and technique was to dream about setting up a theatre company with my flatmates. Our first step was to be a show at the Edinburgh Fringe, with me writing and performing a small, silent role, another flatmate directing and the last two performing.

Inspiration

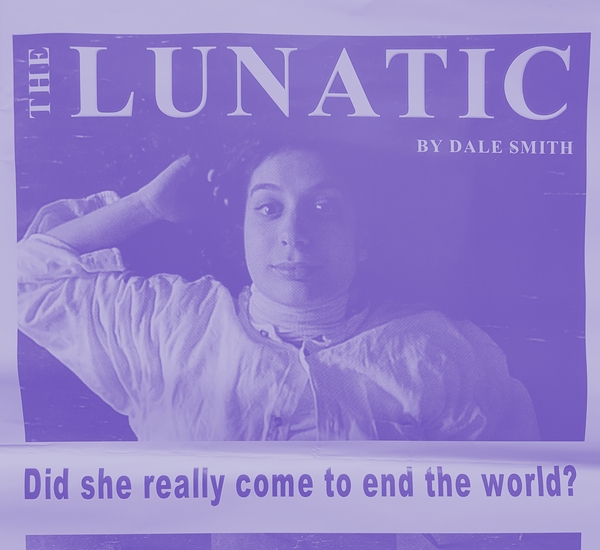

The Lunatic was inspired by Desmond Morris’ The Human Zoo, which depicts a version of humanity damaged and tormented by its inability to adapt its bestial instincts to modern city living. People caged in cities, driving themselves to despair and madness because they deny how little evolution has actually changed them. It was this world that formed the backdrop for the play, and its cast of characters struggling to work out what they were supposed to do with their lives.

The story also grew from the numerous stories of far-right and religious groups claiming that the turn of the millennium would mark the end of the world, and from some research into angels done whilst studying Angels in America. The ending – closing the play before the central character has resolved their own dilemma – was taken straight from Life’s a Gatecrash, under the misapprehension that this marked what “Edinburgh wanted” from a play.

Getting the Story

The story came very slowly, and I had started and abandoned three versions before I finally knuckled down and got all the way through it. Part of the problem was that the two ideas I was working with didn’t belong in the same story. I wanted to write a myth of redemption and forgiveness set in Morris’ hopeless dystopia, and the far-right millennial cult pulled everything into melodrama and farce. I was too close to the story I’d grasped at and too far from the lives I was struggling to write.

As we got closer to our suggested rehearsal dates, one of the actors had to drop out. And then the other. Things got tense between the director and myself: we hadn’t assigned a producer role to anybody, so it tended to fall on both of us to do the little, practical jobs that we both thought someone else should be doing. Added to that, he wasn’t completely happy with the script, and communications broke down to the point where he also withdrew. With everything pretty much in place except the cast and the director, I played the “The Show Must Go On!” card. At the point where the script needed more attention, I set it aside and changed hats.

Editorial

Directing something I had written was difficult. The thing I was most looking for at that stage of my career was validation, some voice of authority to tell me that I had talent, not luck. I expected writing to involve me coming up with a first draft, and then a more experienced editor or director to do my work for me and just tell me which bits worked and which didn’t. And probably tell me how to make them work as well. I had directed before and had no fear of it, and could happily approach a text by some other author and make the cuts and amendments I thought it needed to make it better. But I shied away from doing that as the director of my own work, perhaps because it would have forced me to acknowledge it as something I should be doing as a writer anyway.

Which was a shame, because what the Lunatic needed most was an outside perspective. Everyone who had seen it before it was produced came from effectively the same background and was at the same point in their lives: just leaving University and uncertain about what came next. But I was too close to it to see how much that influenced the story, and how I should have embraced that and let it be what it really wanted to be. It nearly did what I wanted, but just at the last moment … didn’t.

What Happened Next?

I approached people I knew and students in my department at the University to audition for the play, and eventually settled on my new cast. I had wanted a young actor called Jan to play my neo-nazi, having seen him playing Freud in a student production of Hysteria and finding him captivating. Then in the audition I discovered that the German accent he’d had in the play was his own, not the character’s: the idea of a so blatantly German neo-nazi bothered me enough to ask Jan to be our stage manager instead, which again should have warned me that I wasn’t really invested in writing a story about neo-nazis. Or that I should talk to people for five minutes before asking them to audition.

But the cast I finally got proved to be my saving grace: the lead female role was written for Helen Copley (who had been the lead in Life’s a Gatecrash) and she agreed to stay with it even through all the unexpected changes. She shored the production up, encouraging the other actors through suggestions and example, and by the time we started our run things we pretty slick. Then Helen injured her knee during the first week, and we had a rejig: Bex Moss, who had been playing the silent angel part I’d written for myself, bravely stepped up with a day’s rehearsal to take the lead, and made it her own. Jan made it onto the stage, taking over the angel role.

It was tough, especially since everybody we brought to Edinburgh to do the play had a different idea of what we were there to do, but we played to an audience every night but one and came away proud of what we’d done. The reviews we’d earned weren’t strong enough to say we should give up the day job, but they weren’t bad enough to suggest we shouldn’t ever dream of doing this again.

Doing the show crystallised a lot of things for all of us. It killed stone dead the idea of the original gang of us setting up our own theatre company, because we knew that none of us wanted to do the behind the scenes stuff that was essential to making it work. As proud as I was of everything I’d done to make the show happened, I knew my ambition was to write, not to direct and definitely not to produce. I hoped that if I put the same amount of effort into getting a writing career, I’d end up with one. When I came back to University after Edinburgh to do a post-grad in writing, I approached it certain that it was the one thing I wanted to do.

Which may have been why I was the only one of my classmates to sell the script they wrote for that course …