The past has a sepia tint. The streets, the grass, the air: it’s coloured in shades of brown, in the past. People forgot that, once the past was passed. But those who lived there, those who hoarded the seconds to examine in some future moment, never forgot that. They could see it all around them, taste it in the air.

Some were collectors, putting time into individual glass jars with a neatly printed label. They would keep their moments on dusty shelves, each individually catalogued in an equally dusty tome. Rarely was the book consulted, even rarer were the shelves visited, but it gave a certain sense of contentment to know that at any moment, they could be. Should the need arise, the past could be relived, and that surety allowed them to continue on in the present.

Some were merely tourists, taking in the sights and sounds of another’s memories without ever understanding the culture, the nuances. They would wander in, dragging the dusty colours of future time in on their clothing, and take a flash-frame photograph of the event for their album. Sometimes the photographs would be re-examined later, sometimes the film would never be developed. Whichever, at least they could say that they were there.

Arnold Lee was neither of those. He lived in the past, yes. He breathed in its sepia-dust, yes, but he breathed out something different. He breathed out life, colour, vitality: he breathed out the future.

He watched: teams of builders all raised their hammers in seeming perfect synchrony, beads of sweat glistening in the sepia sunlight. On his command - his - each hammer swung down, connecting with the sepia masonry, rending the sepia brickwork. The building was so old - so steeped in history - that its walls were like the thinnest parchment. The heavy heads broke through the bricks, bursting them into dust that flew into the air and masked the rubble from sight. But once the dust settled, each wound in the ancient building would let through the most glorious light, the most brilliant colour.

Each blow brought the future one moment nearer.

‘Oh dear,’ someone sighed mournfully behind him, and Lee found himself in a panic.

His first thought was that something had gone wrong, that somehow one of the mighty hammers had missed in its pendulous motion, and somehow the future was still trapped inside the building’s dusty frame. As his eyes danced over the building site he could see no wrong. Each hammer fell as if triggered by the fall of the last.

Within moments, the crumbling ruin would be nothing but a seed bed for the new. No, there was nothing wrong.

Everything was as it should be.

Except somebody said again:

‘Oh dear oh dear,’

Lee couldn’t help himself: he spun around on the gathered crowd.

‘Is something wrong?’ he asked sharply.

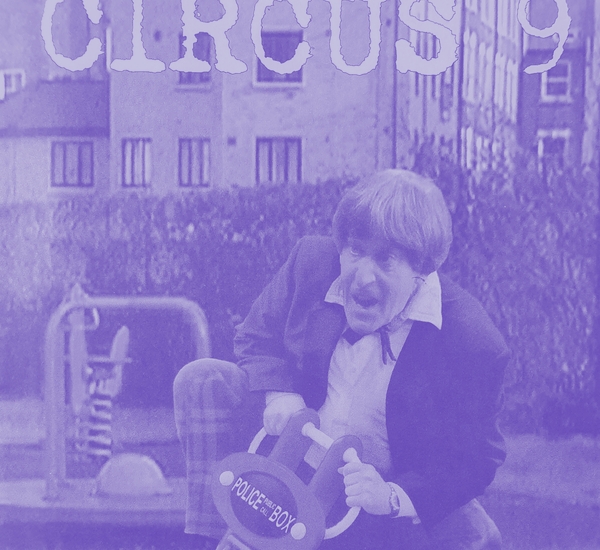

A small man with a puppy-dog face gave him a mournful gaze. His fingers were dancing excitedly in a pristine white handkerchief, even as he let his deep blue eyes return to the building site. The hammers still fell, one after the other.

‘Oh dear, I’m so sorry,’ he said, his unruly mop of thick black hair shaking even as he swayed in apology, ‘I didn’t mean to interrupt. It just seems quite sad, doesn’t it? Such a fine old building, knocked down in her prime.’

Of course, Lee was disgusted.

Lee looked at him. No, no: Lee glared at him. Fire danced in his eyes: he fancied - just briefly - that he could see the little man’s black frock coat smoulder under the intense heat of it, the pin holding his bow tie together melting into water.

‘That building,’ he snapped, letting his finger point in a most ungentlemanly fashion, ‘is a monstrosity. Have you even seen the detailing around the windows? Mock Tudor? What did the Tudors ever know about building pubs anyway? That disgrace should’ve been torn down the second it was built. No, no, it should have been left until today so that when people see my arcade they’ll realise just what should’ve been there all along. That thing is the past. This is the future.’

Lee’s arm swung: his hand barely poked out of his striped blazer as his thin fingers pointed to the sign: Howkins’ Arcade, opening soon. Below the sign, an artist’s impression - a glory of steel and glass. Lee beamed proudly.

‘Oh dear,’ the little man sighed again, and turned on his heels and left.

Lee watched him go, trying his damnedest to keep his jaw tight shut.

Some people, he decided, just lived in the past.

Some time passed. It had a habit of doing that, no matter how you tried to keep track of it. Some days, it seemed like the only reason the keep a calendar was to look back at how many days had slipped through your fingers. Or, at least, that was how it seemed to Arnie Lee.

Take today: he had woken as he had every day, showered, shaved as he had every day, even driven in to work in exactly the same way he had every day for the past . . . ten years? He had breezed into his office heedless of the hour: he was, after all, the boss and where was the point in being boss if you couldn’t turn up late? He had smiled at his secretary and asked for his appointments like he would any day, and she had smiled sweetly back and told him he had a eleven-fifteen with Ralf Wilkins. Nothing wrong with that, no not at all. Until she had said where Ralf wanted to meet.

So Arnie Lee found himself sat in a café on Mount Street, gazing over the rim of a coffee cup at his “greatest triumph” and wondering where the days had gone.

‘Oh my!’ came an excited voice from behind him, pulling his eyes away from the Howkins Arcade.

Stood before him was an imp of a man with a mop of thick black hair, a dark frock coat and a bow tie that was only in place by the grace of a safety pin. Perhaps it was something to do with the memories that were floating around that morning, but Arnie placed him immediately.

‘It’s you, isn’t it?’ he said, fixing the man with his best “Monday morning facing the board” stare. ‘You were there when the Ale House was demolished. Weren’t you?’

The glint in Arnie’s eye dared the little man to say how ridiculous the whole idea was. Instead he smiled, a broad grin which made him seem so much younger than logic dictated he must be.

‘Good morning, Mr Lee,’ he said, a mischievous glint in his eye.

Arnie let out a little snort.

‘God I was a little prig, wasn’t I? Just out of university and insisting every called me “Mr Lee”. It’s Arnie, please.’ inspiration struck: he couldn’t decipher why: ‘won’t you join me for tea, Mr . . ?’

‘Doctor,’ the little man said instinctively, and then looked around guilty. ‘I really shouldn’t. I’m meant to be looking for my friends. They really could be in the most tremendous trouble by now.’

Arnie spread his hands wide:

‘Well, if you can’t spare a few moments for teacakes . . . ’

The imp was torn now.

‘With hot butter?’ he asked, his finger finding its way to the corner of his mouth.

‘What else?’

The little man looked first over one shoulder, then over the other. Next, a broad grin split his face in two, and he sat himself down on the chair opposite. He gave Arnie a conspiratorial wink:

‘Well, just the one . . . ’

After his third teacake, the little man seemed to have forgotten all about his friends, if they even existed. It made Arnie smile to see the way the man would grin with each mouthful he took, the hot butter running down his chin and dripping onto his shirt. Perhaps that was why he remembered the man so vividly: he had been so entertaining on their first meeting. Perhaps that was why the conversation turned so easily to self-deprecation, too, since Arnie couldn’t help but feel like he was speaking with an old friend, despite the fact that the little man must be at least the age of Lee’s father, if not older.

‘Can you believe that blazer I used to wear? I’d never take it off. Thank God I grew out of that!’ he said, looking down at his tastefully tailored suit.

Arnie felt a sudden flash of guilt: his breakfast companion was still wearing what looked like the same clothes he’d been wearing that morning, so many years ago. It must be a new set, of course, but still . . .

A diversion, he said:

‘So what do you think of the Arcade?’

‘Ah,’ said the little man, and fiddled with his fourth teacake for a few moments.

Of course, Arnie was intrigued.

‘It’s very good, you understand,’ the man said eventually. Reluctantly. ‘But the building before it, it had . . . ’

Arnie smiled, already spreading his hands in a placating gesture.

‘I know exactly what you mean. Five thousand we spent on state of the art air conditioning – God knows what that would be in real money – but that damned arcade’s never the right temperature. But the old Ale House, that kept cool twenty-four seven, three six five. I’m still not entirely sure why: I wish I’d checked it out more thoroughly before I sledge-hammered the place.’

‘Why didn’t you?’ the imp asked, demurely looking at the milk jug.

Arnie shrugged:

‘I don’t know now, to be honest. I had this bee in my bonnet, back then. You must have seen: anything over two years old was redundant and ought to be dynamited for the new wave. I would’ve bulldozed the Coliseum if they’d let me, back then.’

The little man looked nervous, as if he was in charge of the security arrangements.

‘And now?’ he said.

Arnie smiled expansively.

‘If you took me back now,’ he said, ‘I’d give Mr Lee a damned good kicking and make sure the old Ale House stayed standing.’

‘Oh good,’ the little man said, grinning widely across his face.

‘Excuse me, Mr Lee?’ said a waitress hovering politely to one side. ‘Your guest has arrived.’

Arnie was about to turn to his original guest and make some light hearted comment about the irony of the waitress’ address, when he realised that the little man had gone.

And still time passed: no matter how he tried to bottle it, to hoard it in jars, time still seemed to want to trickle through his fingers like so many spilt Martinis.

Take today, for example. He’d tried to keep hold of the day in his mind, because somehow it seemed like it should hold resonance. Darn it, it did hold resonance: but still it wouldn’t stay firm in his thoughts. One moment it was a possibility, the next the planning proposals had been filed, and then suddenly the day itself was here. The time that occurred in between slipped and slid like a raw oyster, and of course there was nobody left at either the Howkins Foundation or the Consortium who remembered old Arnold, their benefactor.

Still, somehow he had managed it: the Howkins’ Arcade was being demolished, and he was here to see it.

The bulldozers and the cranes were moving in, wrecking balls picking up speed, as old Arnold reached for the champagne. He’d be paying for it later, and not just from the cuts the bottle would force him to make in his weekly allowance, but it was worth it. Something as monumental as this should be celebrated: the last mark you had made in this life being slowly erased from history. After all, once the arcade was gone, was there anything that might even remind people of who he had been?

‘Ah,’ came a voice that seemed half-familiar, ‘they’re redecorating. I don’t like it.’

Old Arnold looked round, and saw a small framed man with piercing blue eyes and a shaggy mop of greying hair stood behind him, eyeing the demolition work with suspicion.

‘Hello, Arnie,’ he said, and old Arnold snorted.

‘Just Arnold. Makes me sound like I was in Terminator when you call me that,’ he grunted, but inside he was happy. Not only was this someone who knew him from the old days, but they’d bothered to be here to mark the occasion. In today’s here today, gone tomorrow world, that was almost the equivalent of having somebody erect a pyramid in your honour. Arnold smiled a broad smile: the effect wasn’t the same since his teeth had been replaced, but the feeling was there, all the same.

‘You’ve come to see the big event, then?’ he said, his gums flapping over the edges of the words.

The grey haired imp nodded, his crystal eyes catching Arnold’s.

‘Yes. It’s sad, isn’t it.’

Arnold chuckled to himself: a wispy gasp that sounded more like asthma than amusement.

‘Sad?’ he finally managed to gasp. ‘It’s about time. That old thing’s been nothing but an eyesore these last ten years. Good riddance, I say.’

The little man seemed shocked.

‘But you designed it!’ he said, his eyebrows dancing.

‘And what good’d it bring me?’ Arnold gasped. ‘First chance I got, I got out of design and into consultancy. And see where that got me.’

‘But . . . ’ the man stammered, his fingers running into his pockets for shelter. ‘But . . . such a fine old building, knocked down in her prime.’

Arnold was grinning like a lunatic now, his head shaking from side to side.

‘You young pups don’t see it, do you?’ he said, almost laughing. ‘That’s the way of the world, you see. The old gives way to the new. Change. Everything changes. You can’t help it.’

‘Oh dear,’ said the little man, and everything changed.

Something sparked, and memory suddenly blossomed. Lee, Arnie and Arnold suddenly shared the same thought at the same moment, and each remembered where they had seen this strange little man before.

Of course, Arnold was amazed.

He looked again at the little man: his black frock coat, his bow tie held together by the grace of a safety pin, and the greying hair cut to the same style as it had been when it was black and lustrous. He even had the same look of impish embarrassment on his face as he realised that old Arnold had finally recognised him. The little man - the Doctor - dropped his hands into his pockets and looked sheepish.

‘It’s the way of your world,’ he said softly, his eyes still elsewhere. ‘The old gives way to the new. Everything changes, second to second. It’s not the way of my world. Static, solid dependency is the way of my world. Nothing changes: we don’t change. Look at me: I’m still wearing the same clothes I wore when I was born.’

Arnold looked at him: despite everything common sense told him, he didn’t argue.

‘I’ve been selfish,’ the Doctor said finally. ‘I’ve outlived my time. I knew, even then, that my time had come. But I wouldn’t, I couldn’t just . . . Well. Goodbye, Arnold. Thank you.’

And, with that, the little man in the frock coat turned away, leaving old Arnold alone with his memories.

Moments later, the dynamite detonated and the Howkins Arcade settled into dust.